Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma

Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma is common and challenging to treat. Interpersonal violence (mostly alcohol – related), sporting injuries, falls and road traffic collisions account for most of maxillofacial trauma. It can be isolated or part of polytrauma (especially in the context of road traffic accidents).

The assessment and the diagnosis of maxillofacial trauma should be done in context of the ATLS sequence when the patient presents in the accident and emergency department. It can be challenging, and requires an expert input. Overlooking a maxillofacial fracture can result in disfigurement and long term or permanent disability.

Presentation

Patients with maxillofacial trauma present most commonly in weekends, night-time and Monday mornings. Assessment should follow the standard Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines. Airway compromise, major bleeding and visual loss are the key problems to rule out on initial assessment of maxillofacial trauma.

Maxillofacial trauma is often combined with head injury. This may lead to unconsciousness, amnesia, nausea, post-traumatic headache or dizziness. The severity of this can be assessed using the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS). It is crucial that any sort of injury that impacts on GCS is dealt with appropriately prior to dealing with maxillofacial trauma.

Broadly, maxillofacial trauma is divided into soft tissue injuries and bony trauma (fractures)

Soft tissue injuries

These are generally lacerations involving the skin of the face, scalp and neck. It is paramount that any deeper injuries are excluded prior to treatment, as formal exploration (i.e. neck) might be needed. Some significant anatomic structures are at risk (facial nerve, parotid duct, lacrimal ducts). Damage to any of these requires OMFS microsurgical input. Facial lacerations can result in significant disfigurement, unless treated promptly and accurately. Foreign bodies and debris should be removed and wounds washed out, with minimal debridement. The face has an excellent vascular supply. This allows for excellent wound healing provided suturing is precise. Tetanus prophylaxis and antibiotic cover might be needed.

Occasionally, soft tissue injuries can be the result of dog or other animal bites. These cases require copious washout, exploration and debridement, as they are prone to deep and resistant infections.

Bony Injuries – Facial fractures

Any bone of the facial skeleton can sustain a fracture. Most commonly, facial fractures occur on the mandible, zygomas and nasal bones. With the advancements and developments in open reduction and internal fixation, treatment and rehabilitation of facial fractures is rapid and accurate.

Nasal fractures

Nasal fractures are the most common facial fractures. The main cause is interpersonal violence. Swelling may mask any nasal bones’ deformity. Non-treated nasal fractures can lead to significant disfigurement for the patient (‘rugby nose’). Sometimes, nasal fractures can occur in combination with fractures of the ethmoid bone (“nasoethmoidal fractures); these injuries are complex and often require open surgery.

Examination

Your OMFS H&N Surgeon will examine your nose checking for symmetry and mobility. There might be swelling and bleeding. A collection of blood under the nasal septum (called septal hematoma) can destroy the cartilage and requires urgent attention and drainage.

Investigations

Clinical examination is usually sufficient and plain X-rays are generally of little benefit.

Treatment

Manual reduction under local anaesthetic is usually sufficient to treat simple nasal fractures. This should be done as soon as the injury has occurred; however, if 6 or more hours have lapsed, swelling usually settles in and accurate assessment of the reduction is difficult. In that case, your OMFS surgeon will allow for 5–7 days before treatment, so that the swelling resolves. In more complex nasal fractures, manipulation under general anaesthetic and the use of a splint for 2 weeks might be needed.

Mandible fractures

Mandibular fractures are very common. The patient presents with malocclusion (“my teeth aren’t meeting properly”) and significant pain on the fracture side.

The mandible will usually fracture in two places. This is usually the site of direct impact and a fracture in an area opposite this site (indirect). In case of a blow to the midline of the jaw (symphysis), both mandibular condyles (“hinges” of the jaw) can fracture.

Fractures of the condyle of the mandible can easily be missed and result in long-term pain, reduced mouth opening and disability. One should have a high index of suspicion and take the mechanism of the injury into account.

Ideally, mandible fractures should be treated within 48h of presentation, for optimal results.

Examination

Identifying mandible fractures is usually straightforward. Your OMFS surgeon will examine your lower jaw for signs of bony steps; mobile bone fragments, missing teeth, swelling, heamatoma, and signs of malalignment and malocclusion (teeth not meeting as they should). The examination can be painful and your OMFS surgeon will be as gentle as possible. Mandible fractures can injure the mandibular nerve (or its continuation, the mental nerve) and this will present with numbness to the lip and the chin.

Investigations

Plain radiographs (OPG and PA mandible) are usually sufficient to diagnose mandible fractures.

Treatment

Mandible fractures are considered open fractures and should be treated within 48h to avoid infection and osteomhyelitis. Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended.

The vast majority of mandible fractures are treated with open reduction and internal fixation with titanium miniplates.

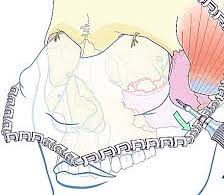

In most cases, access to the fracture side is done via an incision through the mouth. Occasionally, a small incision has to be made to the cheek to allow transbuccal access to the angle of the mandible. For condyle fractures, you may need to have an incision in front of your ear. Very rarely, in complex comminuted fractures, access through an incision in the neck might be required. Your OMFS surgeon will discuss and explain the treatment details with you. The metal work used to treat your fractures doesn’t need removing; it doesn’t set alarms off at the airport. It can, however, become loose or infected, and in that case your surgeon will remove it after the fracture has healed.

Avoid straining, weight lifting, contact sports and having soft diet fro 4 weeks, is paramount after the treatment of mandible fractures. Occasionally, your occlusion (the way you bite your teeth together) needs to be guided for a few weeks, using screws and elastics.

Zygomatic fractures

Zygomatic fractures are fractures of the zygoma (cheek bone). The zygoma bone forms part of the orbit, therefore most zygoma fractures involves the orbit, apart from the cases of isolated zygoamatic arch fractures. Zygomatic fractures are usually the result of a punch or blow on the cheek.

Examination

The initial assessment of these injuries must include an eye examination. As a minimum this examination should include visual acuity, pupillary light reflexes and ocular movements.

An ophthalmologist and an OMFS surgeon should immediately investigate any acute decrease in visual acuity. This might be due to a retrobulbar haemorrhage, which requires urgent treatment to avoid permanent blindness. Early signs of this condition include inability to see the color red, pain in moving your eye, proptosis (eye feels like is pushed out of the orbit) and reduction in visual acuity (can’t see very well).

After exclusion of any acute eye problems, a thorough examination of the face will be carried out. Your OMFS surgeon will feel your facial skeleton for palpable steps, will check your eye movements (to exclude entrapment of the ocular muscles by the bony fragments – this can present as double vision/diplopia) and will feel your cheek for numbness or paraesthesia. This is common, as the infraorbital nerve is usually injured in zygoamatic fractures. The paraesthesia involves the cheek, lateral nose, upper lip, and upper teeth at the site of the fracture.

Facial symmetry is usually disturbed in zygoamatic fractures. The cheekbone on the site of the fracture appears depressed. Your OMFS surgeon will assess this by standing behind you, placing one index finger on each malar eminence and comparing for symmetry.

Occasionally, the mouth opening might be reduced, if the fractured zygoma (especially the zygoamatic arch) is impinging on the coronoid process of the mandible.

Swelling around the eye is very common after zygoamatic fractures, and it can be very dramatic if the patient blows his nose. Patients with suspected zygomatic fractures should not blow their nose, and avoid air travel for at least 2 weeks after treatment. Subconjunctival hematoma (blood-shot eyes) is also a feature of zygomatic fractures.

Investigations

Usually, plain X-rays (OM views from different angles, otherwise known as “facial” views) can show the fracture. However, the gold standard is a CT scan with axial, coronal and sagittal views, with fine <1mm bone cuts.

Treatment

Surgery is usually delayed for 5-7 days to allow for the swelling to settle; however, this isn’t mandatory. In fact, much of the swelling is due to fracture, which once reduced and fixed, aids the swelling (oedema) to resolve. The treatment of zygoma fractures involves accurate reduction and elevation to the pre-injury position and fixation with mini plates.

Your OMFS surgeon might need to do a small cut on the skin of your temple, so that he can insert the elevator and lift your check bone to the correct position. He will then access the fracture sites and place miniplates and screws to fix the fracture. You may need to have a cut in an upper and/or lower eyelid crease, or inside your mouth. Like mandible fractures, the miniplates don’t need to be removed, unless they cause problems.

Orbital fractures

Fractures of the orbit occur commonly in combination with zygomatic fractures, but they can also be isolated. This usually happens after a direct blow to the orbit or orbital rim (i.e. with a tennis ball, cricket ball, ice hockey).

Thorough assessment of the eye is paramount in these injuries (as per zygomatic fractures above).

Examination

Your OMFS will examine and exclude acute eye problems (likeretrobulbar hemorrhage). Subconjunctival (blood-shot eyes) and periorbital haematoma are common. The movements of your eye will be examined for double vision (diplopia) and your cheek for numbness or paraesthesia. This is common, as the infraorbital nerve is usually injured in orbital fractures. The paraesthesia involves the cheek, lateral nose, upper lip, and upper teeth at the site of the fracture. Very rarely, the patient may not be able to move the eye at all. This might be due to bony fragments impinging on the ocular muscles (entrapment). This is more common in kids and young adults, and is associated with nausea, vomiting and bradycardia. It should be released as soon as possible, to avoid permanent damage to the muscles.

If orbital injuries are left untreated, they may result in enopthalmos (sunken eye), hypoglobous (eye globe is lower than it should) and permanent diplopia (double vision)

Investigations

The gold standard is a CT scan with axial, coronal and sagittal views, with fine <1mm bone cuts.

Treatment

Acute injuries like retrobulbar hemorrhage should be treated immediately, and fractures with entrapment within 24-48h. The remaining injuries can be treated 1-2 weeks after the event, to allow for the swelling to settle. Like zygomatic fractures, patients with orbital fractures should not blow their nose.

Not all orbital fractures require repair. Some are treated conservatively. Your OMFS surgeon will discuss the options with you.

Surgery for orbital fractures involves exploration of the orbit, release of the orbital contents from the fracture site and repair of the defect with a titanium mesh or plate. Advanced technology like orbital navigation and 3D printing models now allow accurate treatment of these fractures with minimal risk to the optic nerve and the vision. Your OMFS surgeon will usually access the fracture via an incision in the inner aspect of your lower eyelid (transconjunctival), or utilizing a skin crease on your lower eyelid. The overall cosmetic result is excellent.

Fractures of the maxilla and the midface

Midface fractures typically run along bilateral lines of weakness in the midfacial skeleton, as initially suggested by LeFort. They may be isolated to the maxilla (LeFort I), they may be pyramidal and include the nose (LeFort II) or they may include the orbits and zygomas and the entire midface (LeFort III). However, most of the fractures do not follow the standard patterns of the LeFort classification and present in combinations.

Examination

Maxillary and midface fractures present with significant facial swelling (dish face), bilateral periorbital ecchymosis and bilateral subconjunctival/ periorbital haemorrhages with flattening of the midface. The maxilla is mobile, and the OMFS surgeon will check that by stabilizing the patient’s head by applying pressure over the forehead using one hand, and moving the upper jaw with the other hand. Patients complain of malocclusion (“teeth don’t meet together properly”) and bilateral infraorbital nerve paraesthesia. There might be bleeding through the nose (epistaxis), which can occasionally be dramatic.

Imaging

The gold standard is a CT scan of the facial bones with axial, coronal and sagittal views, with fine <1mm bone cuts.

Treatment

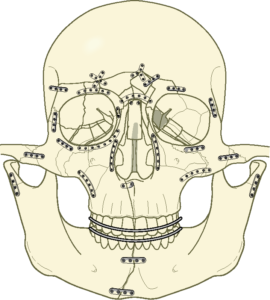

The standard treatment for maxillary and midface fractures is open reduction and internal fixation. Your OMFS surgeon will expose and reduce the fracture and fix it in certain pillars (buttresses) that support the face. The aim is to restore the height and the width of the face and re-create the dental occlusion (which is often easy if the bony skeleton is appropriately reduced). These pillars include:

- Zygomatic buttress

- Lateral nasal wall

- Zygomaticofrontal (ZF) suture

- Zygomatic arches

- Palate (it might be occasionally split)

Fixation follows the same principles as mandible and zygoma fractures, with the use of titanium miniplates. However, the profile of the plates in the midface is usually lower (thinner and smaller plates).

Frontal bone fractures

Frontal bone fractures are more common in patients with large and well-pneumatised frontal sinuses. Most common fracture is that of the anterior table of the frontal bone. The main concern of the patients is the cosmetic defect that this fracture causes. When the fracture involves the posterior table, there is a communication with the cranial cavity, therefore a combined approach and joint management by an OMFS surgeon and a neurosurgeon is needed.

Examination

The deformity is easy to see and palpate. A neurological examination should be considered.

Imaging

The gold standard is a CT scan with axial, coronal and sagittal views, with fine <1mm bone cuts.

Treatment

Posterior wall fractures require urgent joint management by an OMFS surgeon and a neurosurgeon. The aim is to cranialize the frontal sinus (remove the mucosa and the fractured posterior wall, and allow the injured swollen brain to expand in the sinus. A cover with a pericranial flap is also needed.

Anterior table fractures are treated largely for cosmetic purposes. They can be reduced and fixed with miniplates like any other maxillofacial trauma, or can be left to heal and deal with the cosmetic defect at a later stage.

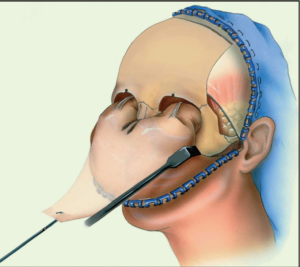

Panfacial fractures

Panfacial fractures are a combination of all the previously mentioned fractures, and they usually represent the result of significant injury (i.e. road traffic accident). They are more often combined with other injuries that might be life threatening and as such their initial assessment and management should be conducted by ATLS guidelines. Once all life-threatening images have been addressed, treatment for the facial fractures can commence, in the form of open reduction and internal fixation. The philosophy behind this treatment is no different than building a difficult jigsaw puzzle.

The main principles in treating panfacial fractures are:

- Adequate exposure of the fracture sides

- Reduction and fixation in a way to restore the height, width and depth of the face (usually work from top to bottom)

- Restore dental occlusion

- Drape the soft tissue envelope

Surgical access is paramount in these complex and difficult fractures. A coronal flap (cut in your hairline and pull the scalp down) might be required to access many areas of the upper and mid face. This sounds and looks dramatic, but it gives excellent access and gives an excellent long-term cosmetic result.

Treatment of maxillofacial trauma emergencies

Retrobulbar hemorrhage

Retrobulbar hemorrhage is an acute condition following zygomatic, orbital, or panfacial trauma. As the name suggests, it is due to bleeding behind the globe (in the intraconal space). It is essentially a compartment syndrome of the orbit. Clinical signs include proptosis (the eye feels pushed out of the orbit), chemosis, ophthalmoplegia (inability to move the eye) and a loss of visual acuity. An early sign includes the inability to see the color red. It can result in irreversible ischemia in less than 2 hours, and requires immediate treatment. The initial medical management includes acetazolamide and steroids, but the definitive treatment is surgical decompression via a lateral canthotomy.

White-eye blowout fracture (entrapment)

White-eye blowout fractures of the orbit (‘trapdoor fractures’) are often missed and this results to significant long-term disability for the patients. They usually occur in children and young patients and may not be clinically obvious. The pathognomonic triad of this injury is painful restriction of eye movement, bradycardia with nausea and occasional vomiting. This is due to the activation of the occulocardiac reflex as a result of raised vagal tone secondary to the entrapment of soft tissue in the fracture line. There is no subconjunctival hemorrhage and the eye appears white (no blood shot).

These injuries must be treated within 48 hours otherwise permanent restriction of ocular motility may occur. The treatment (once the condition is recognized) is simple orbital exploration and release of the entrapped soft tissue. The bony defect is usually minor and often doesn’t need reconstruction. Your OMFS surgeon will usually access the fracture via an incision in the inner aspect of your lower eyelid (transconjunctival), or utilizing a skin crease on your lower eyelid.

Useful links