Cervicofacial Infections

The OMFS H&N Surgeon is often faced with the challenge of dealing with infections in any of the spaces of face, mouth and neck (cervicofacial infections). These vary from very simple dental abscesses to more aggressive forms of spreading infections (i.e. Ludwig’s angina, necrotizing fasciitis) that can be life threatening.

Definitions

Infection

Infection is the invasion of an organism’s body tissues by disease-causing agents (i.e. bacteria, parasites, viruses), their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agents and the toxins they produce.

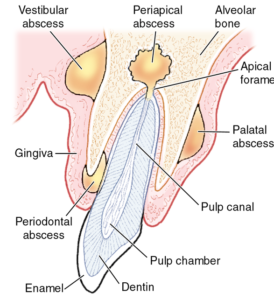

Abscess

An abscess is the collection of pus within the body. If the abscess is formed in a pre-existing body cavity, is called empyema.

What is the best medicine to treat an abscess?

The best “medicine” for abscess treatment is a knife (a surgical scalpel), to incise and drain the abscess.

Cervicofacial spaces

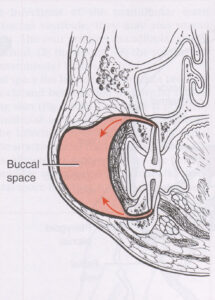

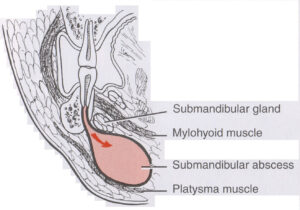

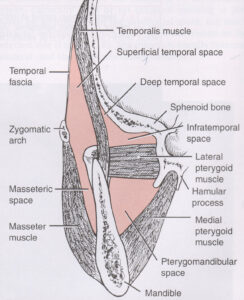

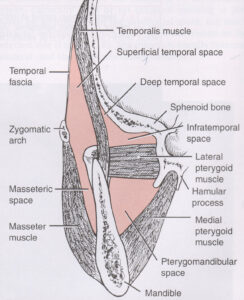

These ‘spaces’ are potential areas, and do not exist in healthy individuals, and become apparent when the muscles or fascia that bounds them becomes stretched or perforated by the pus of a spreading infection.

Some of these spaces are:

- Buccal space

- Buccinator space

- Parapharyngeal space

- Submandibular space

- Sublingual space

- Lateral pharyngeal

- Pterygoid space

- Submasseteric space

- Pterygomandibular space

- Prevertebral space

- Infratemporal fossa

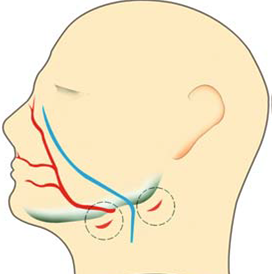

All these spaces communicate with each other; therefore cervicofacial infections are rarely isolated. A dreaded complication of aggressive or untreated cervicofacial infections is distant spread of the infection (downwards, to the mediastinum, or upwards, to the skull base and the brain)

Causes

The majority of cervicofacial infections’ starting point is of dental origin. Anaerobic bacteria multiply at the apex of a non-vital tooth and spread via the jawbone to the above-mentioned spaces.

Other, less common sources of cervicofacial infections include tonsillitis (Quincy – peritonsillar abscess that can spread), sinusitis, neglected trauma (i.e. osteomyelitis from a non-treated fractured mandible), and infection over areas of osteonecrosis (ORN) in previously irradiated patients with head and neck cancer.

Clinical presentation

Patients having cervicofacial infections present with the 5 cardinal signs of inflammation:

- Rubor (redness)

- Calor (heat)

- Tumor (swelling)

- Dolor (pain)

- Functio laesa (loss of function)

Essentially, the patients present with a hot, red, painful swelling in the space(s) that the infection has spread.

Function (i.e. mouth opening) might be limited. The patient might be systemically unwell, showing signs of sepsis (https://sepsistrust.org). Occasionally, swallowing and breathing might be difficult or compromised. These cases represent real emergencies.

Examination

A good medical history is usually enough to direct to the cause of the infection. There is usually a period of preceding toothache or sore throat, and gradually increasing swelling, associated with fever or malaise. Your OMFS surgeon will identify the tooth that has caused the infection; this is often very tender to percuss. Occasionally, more than one tooth can be responsible.

Investigations

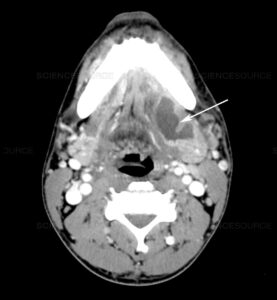

Usually, an OPG is all that is required, in cases of a straightforward dental abscess. However, in large spreading cervicofacial infections, a CT scan is required to reveal the extent of the infection and guide treatment.

Treatment

The first step in managing cervicofacial infections is ensuring that the patient has an adequate airway and can breathe. Rarely, an urgent intervention (like a cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy) may be required. This can be life-saving. In most cases, an experienced anaesthetist can intubate patients with cervicofacial infections, with the help of a camera, while the patient is still awake (“awake fiberoptic technique”).

The main treatment involves incision and drainage of any pus (F8), and surgical exploration and washout of all the spaces that the infection might have spread. Incisions are placed in the neck or inside the mouth or both.

Rubber drains might be placed and left in situ for a few days, until the infection has resolved. Antibiotics are also given (a combination of a penicillin-based antibiotic, like Augmentin, with metronidazole is often employed). There is an increasing interest in testing whether administration of steroids can help in these infections (https://www.bjoms.com/article/S0266-4356(17)30656-3/abstract).

The cause of the infection also needs dealing with. Usually, the responsible tooth will be extracted at the time of the incision and drainage.

Special considerations

Ludwig’s angina

Ludwig’s angina is a type of severe cellulitis involving the floor of the mouth, the submandibular spaces and the neck. The floor of the mouth is hard and raised, and the patient presents with raised tongue and saliva drooling. As the condition progresses, the airway might be compromised. This condition has a rapid onset over hours.

The majority of cases follow a dental infection. It is named after a German physician, Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig, who first described this condition in 1836.

Treatment

- Airway management

Ludwig’s angina is an airway emergency – if the anesthetist cannot secure an airway, a surgical airway (like a cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy) may be required.

- Antibiotics and Steroids

- Surgical Incision and drainage

- Postoperative care and nutritional support

With the appropriate management, the prognosis of this condition has improved significantly.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oRroGqOOdfw

Necrotising fasciitis

Necrotising fasciitis is a rare but serious bacterial infection that affects the tissue beneath the skin, and surrounding muscles and organs (fascia). It’s sometimes called the “flesh-eating disease”. It can start from a relatively minor injury, such as a small cut, but gets worse very quickly and can be life threatening. In the H&N region, it is very rare, but can progress quickly, devitalizing large areas of tissue.

Treatment

The main treatment is surgery to debride the dead and infected tissue.

Intravenous antibiotics and supportive treatment, usually in the context of an Intensive Care Unit, are also given. The prognosis is guarded. Should the patient survives the infection, he might need several reconstructive procedures to restore the defects that have resulted from the surgical debridement.